What a (cool) quantum computer actually looks like

How frozen temperatures influence the design of quantum computers

I recently realized that “What does a quantum computer actually look like?” is often an overlooked question, especially given that quantum labs, such as the Google Quantum Lab in Santa Barbara, California, are so inaccessible that even most quantum software engineers have not visited one.

The common visualization of quantum computers isn’t exactly how they actually look in a real quantum lab. The quantum computer itself accounts for a very small part of the overall system. Its operation at very low temperatures is hardware, space, and cost-intensive, limiting its mass adoption.

This article begins by describing the temperature conditions required for a quantum computer. It then debunks the common visual representation of a quantum computer while explaining how low temperatures shape its design and hardware requirements.

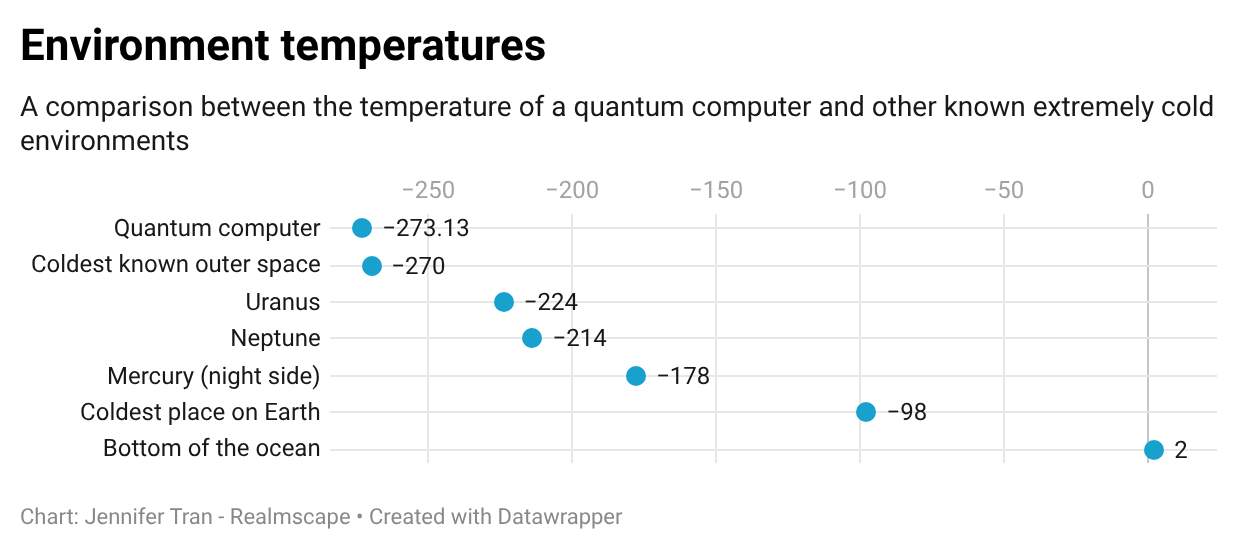

Colder temperatures than anywhere in the universe

The underlying physical environment that powers a quantum computer is highly sensitive to heat, therefore requiring storage at temperatures colder than anywhere in the universe.

A quantum computer operates at temperatures between 10 millikelvins (- 273.14 °C) and 100 millikelvins (-273.15 °C).

Other extremely cold places are warmer than a quantum computer.

The coldest place on Earth, in the East Antarctic Plateau, has a temperature of -98 °C.

The bottom of the ocean, with no access to sunlight, is between 1 °C and 2 °C.

It’s colder than all outer planets: Mercury reaches -178 °C, Uranus drops to -224 °C, and Neptune is at -214 °C. Even the coldest temperature in the outermost space is -270 °C.

Why so cold

Quantum computers operate at such low temperatures because even minor exposure to heat can cause them to lose their quantum properties.

Quantum computers are considered so powerful because they can perform multiple computations simultaneously. This is possible because they can exist in states 0 and 1 simultaneously, unlike traditional computers, which can be in only one state at a time, as noted in a previous article on qubit states.

Any heat exposure could cause a quantum computer to experience decoherence, or lose its ability to run parallel processes.

Therefore, the temperature of a quantum computer wasn’t chosen at random.

Zero Kelvin is absolute zero, the theoretical lowest possible temperature, where there is a total absence of heat. The temperature of a quantum computer ranges from 10 millikelvins (0.01 Kelvin or -273.14 °C) to 100 millikelvins (0.1 Kelvin or -273.15 °C), remaining just above absolute zero but as close as possible without the collapse of atomic motion.

Researchers are working to develop quantum computers that operate at room temperature, which is critical for mass adoption, but still face challenges.

A recent study showed that qubits began to degrade at 170 millikelvin (0.17 Kelvin, or -272.98 °C) [3].

The highest temperature at which a quantum computer still shows quantum properties is just above 1 Kelvin (-272°C), which is only slightly warmer than the warmest temperature at which quantum computers have been known to operate [2].

Debunking the common visual

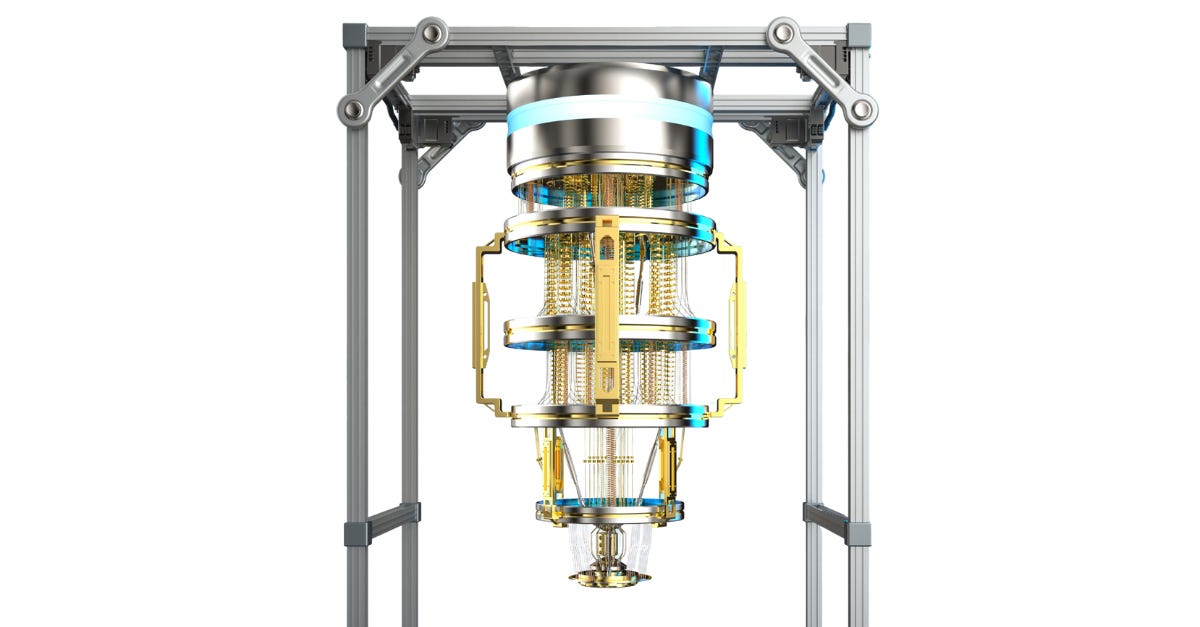

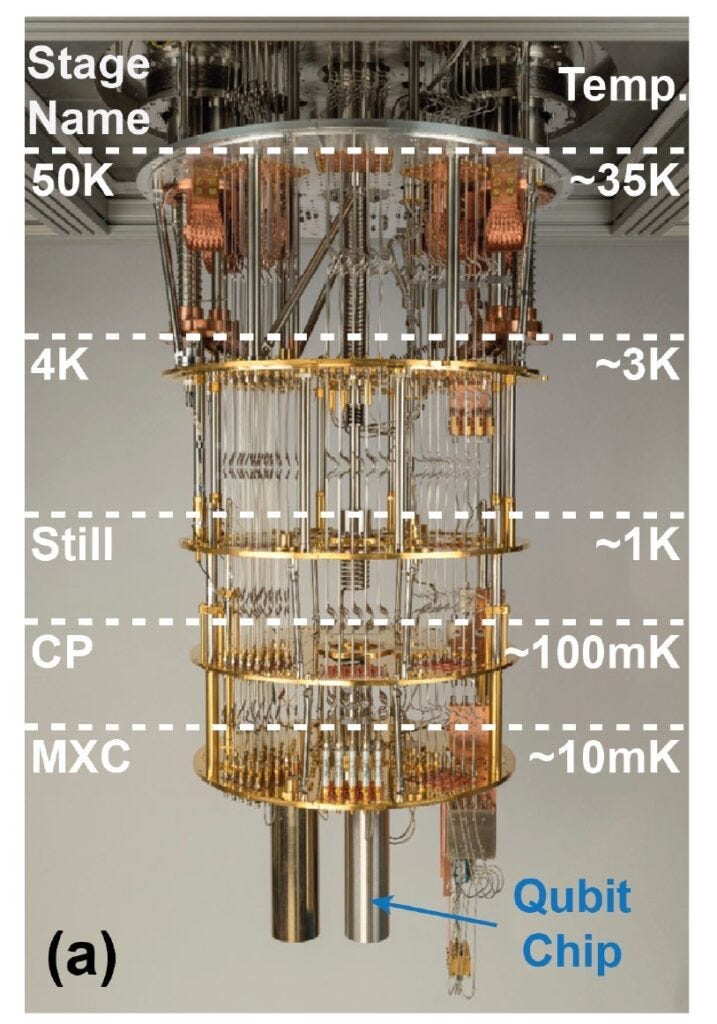

A quantum computer is often visualized as a tall, cylindrical structure with golden stacked plates of decreasing size, connected by wires and rods, mounted onto a support frame, as shown in Figure 1 below.

But the cylindrical structure isn’t the “computer” that performs computation, nor is it exposed like this. Most of it is a refrigerator, and its actual design is based on the unimaginably low temperatures at which it must operate.

Quantum computer components

The components of the visual representation include the actual quantum “computer,” which comprises quantum chips and a quantum processing unit (QPU); a refrigerator to keep the quantum computer cool; and a support frame mount to allow proper thermal transfer.

The quantum chips and QPU make up the smallest part, while the refrigerator takes up most of the space.

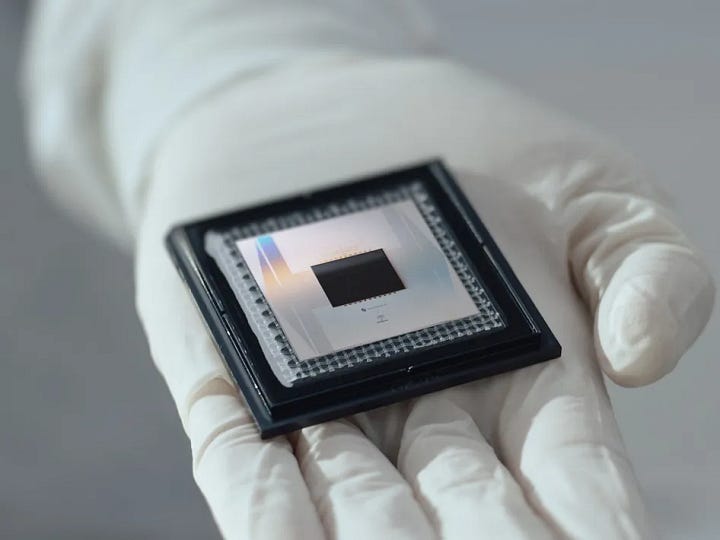

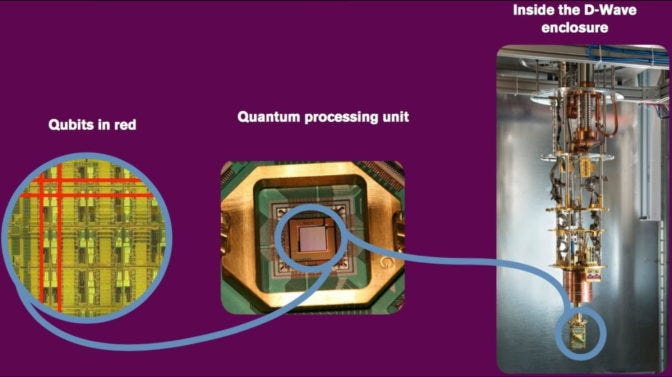

Quantum chips

A quantum chip routes signals between qubits, the most fundamental unit of a quantum computer. It’s the size of a poststamp, or sometimes it is described as the size of an After Eight Mint square.

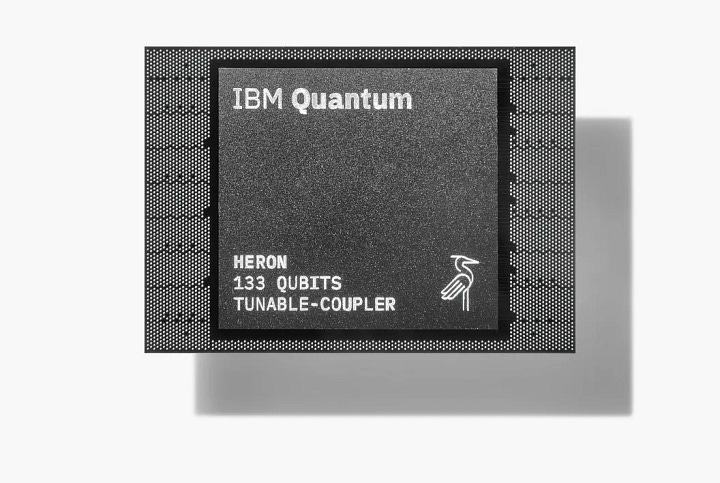

Google’s Willow chip contains 105 qubits. Microsoft’s Majorana 1 chip has 8 qubits, while IBM’s fleet of chip types includes Eagle with 127 qubits, Heron with 133 or 156 qubits, and Nighthawk with 120 qubits. In 2023, IBM also launched Condor, featuring over 1,000 qubits, but it no longer appears on the IBM website.

Quantum processing units (The “computer”)

Dozens of quantum chips make up a quantum processing unit (QPU). A QPU, what we often think of as a “computer,” handles computation, just as a CPU does in a classical computer. It is the size of an end table and is positioned at the narrower bottom of the stacked cylinder [5].

There is no standardized metric for evaluating quantum processing power, so it’s unclear how much compute a given QPU can handle.

Keeping the computer cold

The low temperatures required to operate an error-free quantum computer introduce hardware, physical space, and cost constraints, which are among the reasons for the slow adoption of quantum computing.

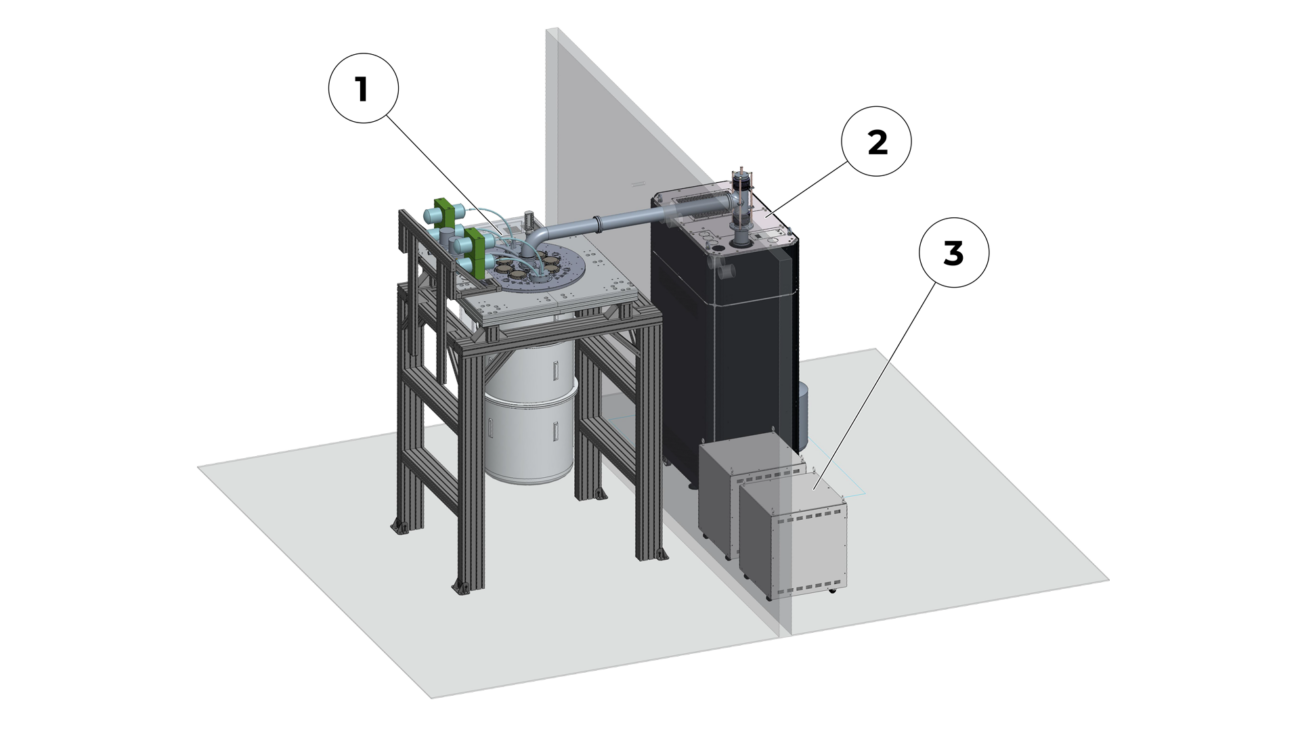

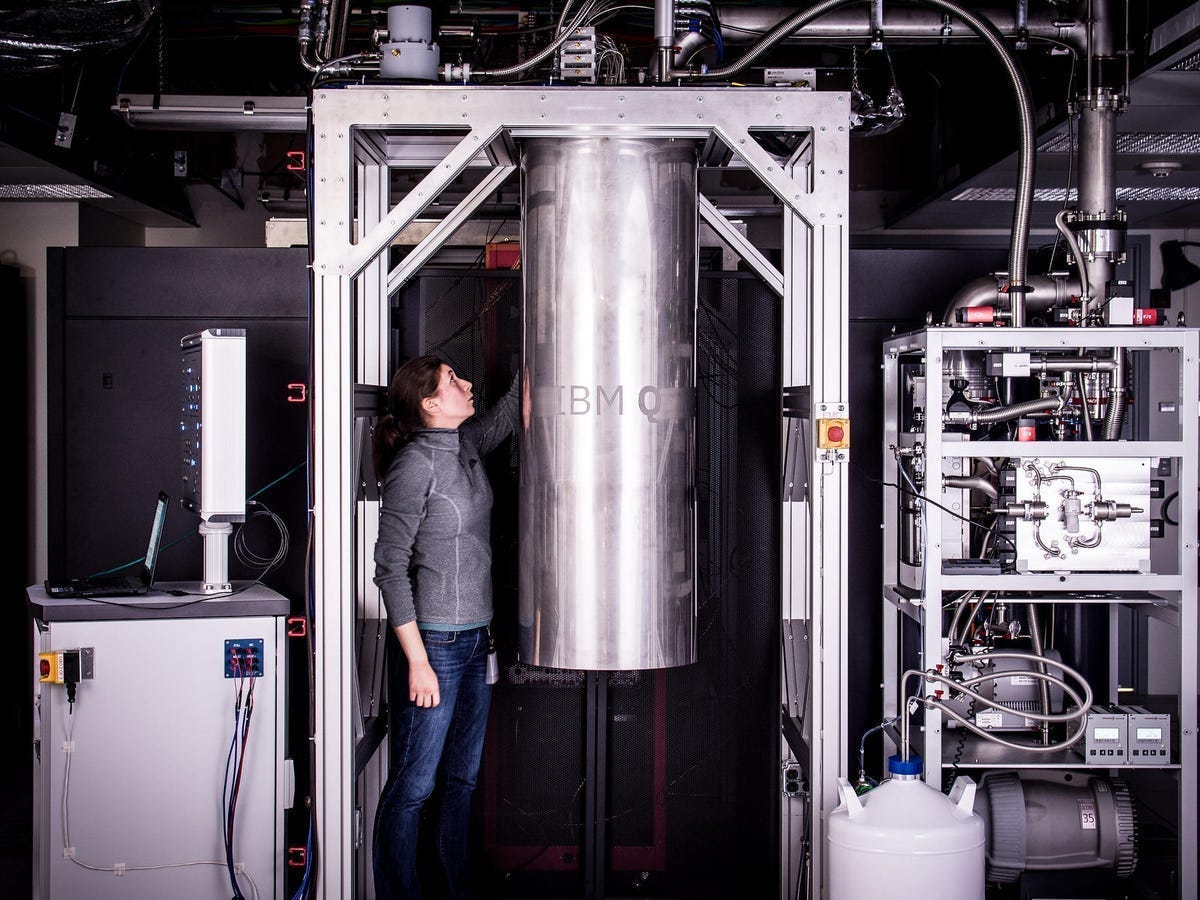

The main component, measuring two meters in length, is a commercial-grade dilution refrigerator (sometimes referred to as a cryostat) that keeps the quantum computer at frigid, unimaginably low temperatures, as shown in Figure 5 below.

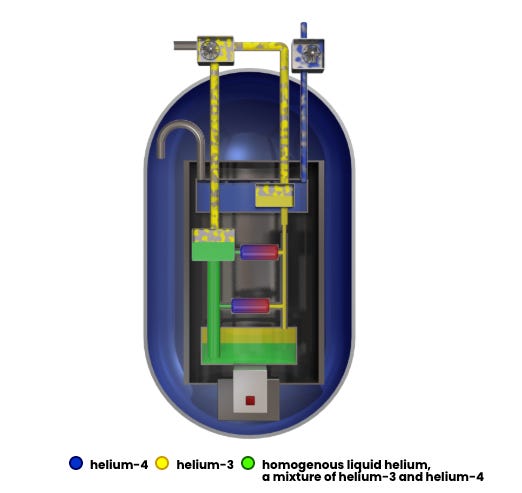

The dilution refrigerator is used instead of a common food refrigerator because it can mix Helium-4 and Helium-3 atoms to become liquid helium, which is considered the coldest liquid on Earth.

The dilution refrigerator is connected to a gas-handling system that pumps in Helium atoms and a pulse tube compressor that can cool the Helium, as shown in Figure 6. The dilution refrigerator is so tall because it is a stacked system that pumps and mixes Helium atoms to produce liquid helium.

At the top of the refrigerator, the system pumps in Helium-4 and Helium-3 at room temperature (shown as Stage Name: 50K in Figure 8). Immediately below the pumps is a section of coolers (shown as Stage Name: 4K in Figure 8), followed by another section where Helium is vaporized (shown as Stage Name: 1k in Figure 8). The gas is sent to a mixing chamber, where it continues to cool, becoming liquid helium at temperatures near absolute zero. The mixing chamber with liquid helium is the coldest part of the dilution refrigerator, where the QPU, the “quantum computer,” is actually stored (shown as Stage Name: MKC in Figure 8).

The entire Helium cooling process is shown in Figure 7 below.

To maintain a low temperature, the dilution refrigerator is mounted onto a support frame to prevent vibrations from generating heat.

In a quantum lab, the entire system, including both the refrigerator and QPUs, is not exposed, as commonly depicted in Figures 1 and 5. Instead, it is covered and held within a nested, cylinder-like metal vacuum can.

So, the system in a lab does not look like the one shown in Figure 9; it is shown that way only for demo purposes.

The system will look more like Figures 10 and 11, completely covered with a metallic cylinder.

This video partially shows the assembly of a dilution refrigerator, highlighting its complexity and size, including its height, which is taller than all of the engineers assembling it:

The cost of a dilution refrigerator

Owning and maintaining a dilution refrigerator is extremely expensive.

One refrigerator costs between 300,000 and 1 million USD, with more specialized units costing more. A typical dilution refrigerator consumes 5–10 kilowatts of electrical power continuously, 24/7, amounting to about 43,800–87,600 kilowatt-hours per year, or about the yearly energy consumption of four to eight American households [1].

Low end (5 kW):

5 kW × 8,760 h = 43,800 kWh per year

High end (10 kW):

10 kW × 8,760 h = 87,600 kWh per year

Energy consumption of an American household = 10,800 kWh

43,800 kWh / 10,800 kWh = 4.0 American households

87,800 kWh / 10,800 kWh = 8.0 American householdsWhile most quantum labs do not disclose their total number of quantum computing systems, an IBM Quantum data center near Stuttgart, Germany, began hosting two quantum computers in summer 2025 and has capacity for up to 12.

A typical quantum lab contains equipment worth hundreds of millions of dollars, which partly explains why most quantum software engineers have never been to one.

If you are interested in visiting one virtually, below is a tour video of an IBM Quantum Lab, or view the Google Quantum Lab virtual tour.

Conclusion

The low temperatures at which quantum computers must operate, and the hardware, physical space, and cost constraints required to keep them at these temperatures, are barriers to their mass adoption.

Quantum labs are very much inaccessible to the public, and even most quantum hardware engineers haven’t seen a quantum computer.

The typical visualization of a quantum computer includes many components beyond the quantum processing unit.

The QPU accounts for a very small portion of a typical visual representation of a quantum computer. Much of the structure shown is actually a dilution refrigerator that keeps the quantum computer at near-absolute zero.

Additional Sources

SpinQ. (2025b, May 30). Dilution Refrigerator: Everything You Need to Know [2025]. SpinQ. https://www.spinquanta.com/news-detail/the-complete-guide-to-dilution-refrigerators

Bhat, H. A., Khanday, F. A., Kaushik, B. K., Bashir, F., & Shah, K. A. (2022). Quantum Computing: Fundamentals, Implementations and Applications. IEEE Open Journal of Nanotechnology, 61–77. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=9783210

Lvov, D. S., Lemziakov, S. A., Ankerhold, E., Peltonen, J. T., & Pekola, J. P. (2025). Thermometry based on a superconducting qubit. Physical Review Applied, 23. https://journals.aps.org/prapplied/pdf/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.23.054079

Components of the dilution refrigerator measurement system. Bluefors. (2023, February 14). https://bluefors.com/stories/components-of-the-dilution-refrigerator-measurement-system/

Google. (n.d.). Discover the Quantum AI Campus. Google Quantum AI. https://quantumai.google/learn/lab